What I’m writing about this week, #18: The Mongol war machine

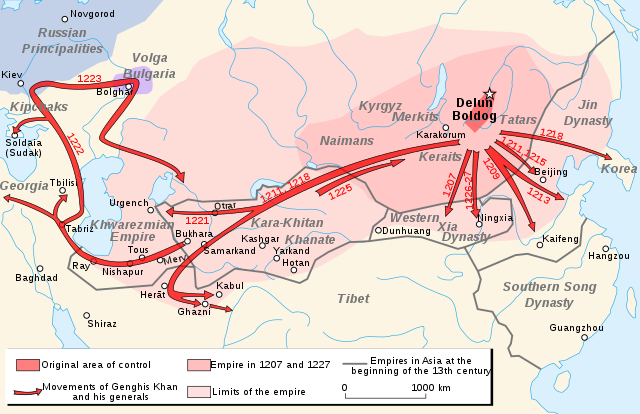

The medieval world had never seen anything like the Mongol army. These brutal, mostly illiterate horsemen erupted out of the barren steppe at the beginning of the 13th century and, over the next forty years, conquered everything before them including what is now China, Central Asia, Iran, Iraq and Eastern Europe as far west as the borders Austria. The Mongol army was a truly extraordinary force, which was one of the many reasons I wrote Templar Traitor, the first historical fiction novel in my Mongol Knight trilogy, which is based on the true story of an Englishman, a Templar knight, who fought in the Mongol ranks for more than twenty years.

The Mongol Empire was nine million square miles at its peak, the largest ever contiguous empire. A man with a prized Mongol “passport” (a bar of silver or gold called a gerege) could ride from Korea to Hungary in the mid-13th century and remain inside the domains of the Great Khan. He would also be able to claim food, drink and fresh horses every twenty or so miles on that five thousand-mile journey.

How did the Mongols manage to conquer such a vast empire?

The heart of the Mongol army was the steppe horseman, a simple herdsman, a rugged individual, habituated from birth to extremes of weather and temperature, used to riding long distances and surviving on very little food and water. His horse, a steppe pony, a broad headed, stocky animal, was very tough too: in winter, they could scrape away snow with their hooves to get to the grass or moss buried underneath. But it was Genghis Khan, a ragged outcast from an obscure clan, who took these simple herdsmen from many different steppe tribes and after much blood, toil and struggle, welded them into an revolutionary new type of army that could out-march and outfight any force in the medieval world.

Genghis Khan (below) organised his army decimally, in groups of ten. Ten horsemen made an arban, the basic military unit. The arban lived together in the same ger (round felt tent), cooked together, fought together. If one man in the arban fought badly, or proved to be a coward, the whole arban was punished.

Ten arbat (the plurals take a T at the end) make up a jagghun, a company of about a hundred men, under a captain called an akhmad, and ten jagghat (1,000 men) makes up a battalion-sized unit called a mingghan, commanded by an officer called a noyan. Ten mingghat made up a tumen.

A tumen of 10,000 horsemen was a formidable, division-sized force, but they were often grouped together in threes or fours to make an army under a commander called an orlok (ie, a general).

arban – 10 horsemen

jagghun – 100 horsemen, commanded by an akhmad

mingghan – 1,000 horsemen, commanded by a noyan

tumen – 10,000 horsemen, three or more tumet were commanded by an orlok

Originally, the Mongol army had nothing but cavalry, but fighting in the various the Chinese kingdoms swiftly taught them the value of siege engines to take down city walls, and the skilled engineers who manned them. They soon incorporated Chinese (and other) engineers in their armies to great effect. And later introduced infantry, often prisoners or volunteers from captured lands. But siege trains and foreign infantry moved slowly, and the core of the army remained two kinds of Mongol cavalry – light and heavy.

Light cavalry

Mongol light horsemen were fast moving and only lightly armoured, if at all. Most wore only a deel, a heavy woollen Mongol robe over a silk shirt, baggy trousers and reindeer-skin boots, a fur-lined hat for protection. But they were armed with swords, javelins and daggers and every man carried the powerful recurved horn-and-sinew bow and up to sixty steel-tipped arrows, and each man was an expert archer.

In battle, the light cavalry mingghat screened the heavy cavalry in the front, sides and rear. The favoured tactic was an advance then a feigned “panicked” retreat by the light cavalry. They would entice the enemy to break their ranks and charge after them, thinking they had broken the “fleeing” Mongol force. The scattered enemy would then be charged by disciplined formations of heavy cavalry, and destroyed.

Heavy cavalry

The Mongol heavy cavalry was well armoured, wearing steel helms with aventails and long padded leather coats sewn with small iron plates, with shoulder protectors and sometimes greaves. There were as well protected as their contemporary Western knights, and their horses (stronger animals to carry the extra weight) were equally well-armoured. Heavy cavalrymen carried long lances with keen steel blades and hooks behind the blade to pull enemies from their horses. The also carried swords, maces, daggers, lassos and every man carried the recurved bow (sometimes two bows) and quivers full of arrows.

Fire in movement

Speed and concentrated force were key to the Mongol success in battle, along with what we would today call “fire-power”. The enemy lines would be attacked with dense showers of arrows from the light cavalry, the Mongols shooting from the saddle in any direction, including to the rear, then the heavy cavalry would then smash into them with all their weight and power. The Mongol had a reputation for always having superior numbers, because each horseman travelled with a string of steppe ponies, sometimes as many as nine remounts per man, and never fewer than three. This gave the impression that Mongol armies were far more numerous than they actually were. It also meant that they could move with astonishing rapidity, with riders changing horses frequently when their beasts became exhausted.

Wives and children, as well as their herds of sheep, camels and goats travelled with the Mongol army, so that they were able to support themselves with meat and milk on long journeys. This was much harder for European (or Persian or Chinese) armies of the day which required great trains of food and fodder to accompany the column to feed the trudging peasants and nourish the great warhorses of the knights.

Training and battlefield communications

The Mongols practiced something called the Great Hunt each winter, partly for food but also as a training exercise for new recruits into the Mongol mingghat. A vast area of land was marked out, sometimes hundreds of square miles, and many thousands of Mongol riders would line up at the starting point, making a line of horsemen sometimes ninety miles long. The line would then advance, with the flanks going faster to curl around like two great arms and join to make a huge circle. Inside the circle, all the wild game of the region were trapped – all kinds of fauna from lynxes to antelope, hares to yaks, leopards to wild goats were encircled. And then this noose began to gradually tighten around the frightened prey.

The Mongol hunters were not allowed to kill the trapped beasts, nor to let the increasingly panicked animals to escape. They communicated with each other with swift riders and also visible signals such as a system of coloured flags, rather like semaphore. These flags were also used in battle, as was the encirclement manoeuvre of the hunt. When the animals were all trapped in a concentrated mass in the centre of the ring, the Great Khan would choose which animals he wished to kill and once that was done, the rest of the Mongol army began a mass slaughter of the captured beats. The Great Hunt taught discipline, communication, and the agility to stop terrified animals from escaping. All valuable in warfare.

The Mongols used other techniques in warfare that were unique to their culture. The cavalry would throw fire-pots – clay vessels filled with burning straw and tar – to create dense smoke banks and deliberately obscure visibility on the battlefield, causing confusion. When the communicating flags could not be seen, they used “whistle arrows” that made a sound as they passed, telling units to advance or retreat.

Psychological warfare

Perhaps the greatest weapon in the Mongol armoury was what we would now call psychological warfare or psyops. They created terror wherever they went with lurid tales of their brutality and ruthlessness and this gave them a great psychological advantage over their enemies. It was common practice, when the Mongols approached an enemy city, to give the inhabitants an ultimatum – I call this the Great Khan’s Choice in Templar Traitor – the choice of immediate surrender or complete annihilation. If the enemy defied them, the Mongols would bring up their siege engines, knock down the walls and, once inside the city, they would slaughter every living thing inside, from cats and dogs to pregnant women. They would make enormous pyramids from dripping severed heads of their foes, and the story of their blood-thirsty barbarism would surely make its way to the next town in their path. And when they presented the new town with its ultimatum, the terrified inhabitants were that much more likely to surrender without a fight.

It was innovative tactics and strategy such as these that allowed Genghis Khan’s hardy men to fight and conquer over such a vast area of the world. The Great Khan was also aided by many gifted commanders, such as Subutai, who led a celebrated reconnaissance-in-force west through Persian, north over the Caucasus Mountains and back east along the top of the Caspian Sea to what is now Kazakhstan. A journey that laid the groundwork for the astonishingly successful invasion of Europe from 1236 onwards.

If you would like to know more about the Mongol war machine, and follow the story of Robert of Hadlow, the Englishman who fought for Genghis Khan, then I suggest you buy a copy of Templar Traitor, which is out now and available from Amazon, Waterstones and all good bookshops. You might also like to know that Templar Assassin (Mongol Knight, Book 2) will be out next summer but can be pre-ordered now.

Comments (0)